Dante Alighieri

Commedia.

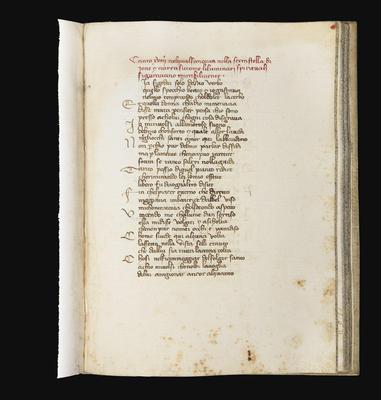

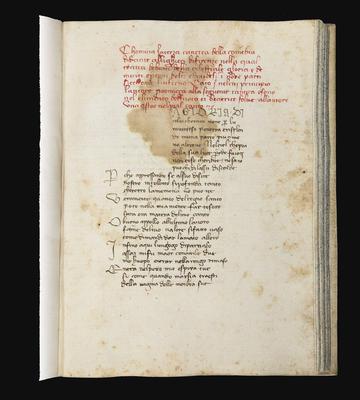

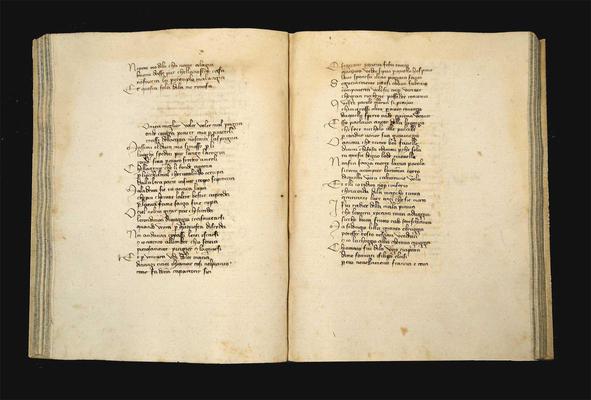

Manuscript on paper. Tuscany (Florence?), late fourteenth century.282x205 mm.iii+199+ivleaves. Fourteen quires. Collation: 114-3?(1/1-2 probably blanks lacking; 1/13 originally blank lacking; 1/14 originally blank, later re-used by hand B for textual additions), 216, 38-1(only 3/1 written by hand A; 3/2-7 originally blanks, subsequently re-used by hand B for textual additions; 3/8 lacking), 4-716, 820 (8/19-20 blanks), 9-1316, 142-1(14/2 lacking). Two blank leaves inserted in the eighteenth century to facilitate arrangement during binding (respectively between fols. 10-11 and fols. 34-35), uncounted in the foliation and collation. Text block: ca. 180x108 mm, one column, 30 lines (for the principal scribe, copying in the fourteenthcentury); one column, 36 lines (for the fifteenth-century scribe; only fol. 11v in two columns). Ruled in coloured ink. In the second and third cantiche fourteenth-century quire signatures, in arabic numerals, at the bottom of the final verso of each quire and the first recto of the following. The sequence of the signatures runs in reverse: the number signed on the recto of the first leaf of each quire matches the number found on the verso of the last leaf of the preceding quire. Written in a minuscule chancery script datable to the last decade of the fourteenth century. A different hand, datable to the third quarter of the fifteenth century, is responsible for fols. 11r-v, 28v (line 13)-34v, written in a small mercantesca script. A third hand, datable to the third quarter of the fifteenth century, is responsible for adding the six verses lacking on fol. 10v, written in mercantesca with a half-cursive ductus. Red ink captions only in the third cantica, added by the main scribe. Blank spaces for capitals, in the first and third cantiche with guide letters, and arabic numerals indicating the running numeration of each canto(partly trimmed). Eighteenth-century vellum, over pasteboards. Smooth spine, inscribed in capital letters at the top ‘Dante M[anoscritt]o'. Edges speckled green. The first ten leaves mounted, with old repairs; a few stains and a pale waterstain to the upper margin, not affecting the legibility of text. In the third cantica a few captions in red ink somewhat faded or smudged. A cut in the gutter of fol. 35, a hole in the lower portion of fol. 128. Marginalia in four different hands, datable from fifteenth to nineteenth century. Rough ink drawings datable to the sixteenth century on the lower margin of fol. 16r (a coat of arms with cross and Florentine fleur-de-lys) and fol. 167r (a long-haired figure wearing a hat); a few maniculae.

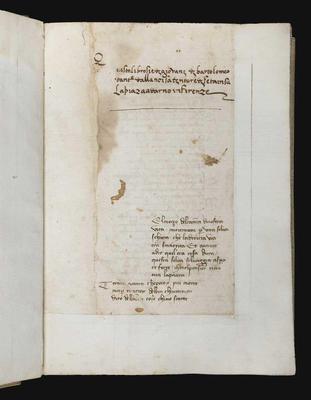

Provenance: the silk weaver Giovanni di Bartolomeo d'Antonio dall'Ancisa (sixteenth-century ownership inscription on the recto of the first leaf of the text, ‘Questo libro si è di Giovani di Bartolomeo d'Antonio dall'ancisa tintore di seta in su la piaza ad Arno, in Firenze'; in the same hand the annotation “Dante Aldigieri, figlolo non so di cui, | mia madre sa di cu' figlolo i' fui”, on a paper strip pasted in the upper margin of fol.iiir); Cioni-Carrega family; Livio Ambrogio collection.

A truly remarkable late fourteenth-century manuscript of the Commedia, possibly produced in Florence but certainly belonging from a textual point of view to the Tuscan tradition of the transmission of Dante's poem. Although there are some contaminations from other branches of textual transmission, it is most closely related to the group of codices derived from the so-called Cortonese (the famousms88 of the Biblioteca dell'Accademia Etrusca in Cortona, copied not later than 1350).

The manuscript was written by a single fourteenth-century scribe, supplemented with later additions by two hands datable to the fifteenth century. It contains an almost complete text of the Commedia; the second and third cantiche are complete (except for the last verses 91-145 of Cantoxxxiiiof the Paradiso, which were written on the last leaf of the manuscript, now lost). The lacunae relate to the Inferno and were in all likelihood missing from the antigraph used by the principal copyist of the volume, writing in the fourteenth century. This is evident from the way the scribe copied the text with extreme regularity, filling each page with ten terzine (thirty lines), only to come to a sudden halt at the first of the two gaps, leaving the rest of the page blank. Taking into account both that the Paradiso and Purgatorio are complete (the Paradiso also includes the rubrics in Italian which precede each canto) and that the quires containing these two cantiche are, as described above, signed beginning with the final quire revealing that the fourteenth-century scribe copied backwards from the last canto of the Paradiso, it seems logical to suppose that in the antigraph he was using the Purgatorio and Paradiso were complete but the Inferno was possibly missing certain portions of the text. Thus he took the decision to start copying from the end of the work in the hope that in the meantime he would find another manuscript edition of the Commedia which would enable him to fill in the gaps in his copy of the Inferno. Indeed, the Inferno in the present manuscript has only one regular quire of sixteen leaves entirely filled in the hand of the fourteenth-century scribe A; the other quires were left with blanks which the later scribe B has partially filled in with the missing portions of text. The lacunae relate to the last four verses of Cantoiv, the whole of Cantov, the first eight terzine of Cantovi, the last nineteen terzine of Cantoxiii, and the following twenty-one cantos of the Inferno. On leaf 11 left blank by the main copyist, the second scribe (hand B) added verses 64-142 from Cantovand the first eight terzine of Cantovi; he also copied the verses 94-151 of Cantoxiii, the cantosxiv-xv, and the first thirty-seven terzine of Cantoxvi, on leaves left blank on purpose. At the end of Cantoxvia note in a nineteenth-century hand has pointed out the lack of the following cantos of the Inferno: ‘mancanootto terzine di questo canto decimo sesto e gl'altri diciotto dell'Inferno per intiero'. A third scribe (hand C) was responsible for the addition of the six verses lacking from Canto 4 (fol. 10v). Therefore, in this manuscript, quite exceptionally in the context of the manuscript tradition of the Commedia in the last quarter of the fourteenth century, the third cantica is complete. Furthermore, the only cantica in this manuscript to have vernacular rubrics is the Paradiso, for each of the thirty-three cantos and copied by the fourteenth-century scribe in red ink. It is especially noteworthy that these vernacular rubrics belong to the earliest type found in the Florentine manuscript tradition, of which the first witness is ms1080 of the Biblioteca Trivulziana in Milan, produced in Florence and dated 1337. According to Petrocchi this type of rubric is characteristic of the earliest circulation of Dante's great poem. It is known that the Paradiso was composed between 1318 and 1321, and these very early rubrics could have been written by contemporaries while Dante was still living.

The manuscript was owned in the sixteenth century by the Florentine silk weaver and tintore (dyer) Giovanni di Bartolomeo d'Antonio dall'Ancisa, as attested by his ownership inscription on the recto of the first leaf. The Florence State Archives hold several documents which provide biographical details on this owner. Giovanni dall'Ancisa belonged to the Florentine mercantile class. His father Bartolomeo lived in the district of Santa Croce near the ‘Gonfalone Bue', and he too was a weaver, or tintore of silk. He managed a small shop, and his clientele included Cosimo de' Medici the Elder. In 1458 Giovanni is not yet listed in the so-called Boche, i.e. the list of the family members economically dependent on Bartolomeo. His name appears for the first time in 1480, after his father's death, in a land registry document. In 1480 Giovanni was only seven years old: therefore he was born in 1473. This fiscal declaration was written by Francesco di Paganello Filipetri, anothertintore di seta, who also exercised the profession of copista a prezzo (i.e. a jobbing copyist). Manuscript copies of the Commedia have been attributed to Paganello's hand (e.g. Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana,ms1047; and Biblioteca Laurenziana,msPlut. 40.33), as well as copies of Boccaccio's works (e.g. Biblioteca Laurenziana,ms107). This manuscript is an outstanding example of the circulation of the works of the great Italian authors in the milieu of the Florentine setaioli. Francesco di Paganello Filipetri might also have had a part in the transmission of the present manuscript to Giovanni dall'Ancisa.

An additional noteworthy feature in this manuscript is the paper slip, which was probably cut from one of the original first blank leaves and is now pasted on one of the preliminary leaves, on which the sixteenth-century owner has annotated the following couplet:

'Dante Aldigieri, figlolo non so di cui,

mia madre sa di cu' figlolo i' fui'

These verses accuse Dante of being an illegitimate child, and are related to the famousTenzone between him and Forese Donati. This lively poetic exchange was made up of three sonnets from Dante to Forese, and three from Forese in response. This remarkable annotation reveals the enduring popularity of the Tenzone in Florence at the beginning of the sixteenth century.

This manuscript is extraordinary evidence for the way Dante's poem was read by the wider public of merchants and skilled artisans, who were literate in Italian (but not Latin) and who often learned to read and write using the Commedia.