Dante Alighieri

Comento di Christophoro Landino Fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Danthe Alighieri poeta Fiorentino...

Brescia, Boninus de Boninis, de Ragusia, 1487.Folio (337x239 mm). See the previous item for the bibliographical description. [298] of [310] leaves, wanting fols. &1-8, a1, a7, D2 and the blank L6. On fol. a2r seventeen-line capital initial ‘N' supplied in brown ink Eighteenth-century half-vellum, boards covered with decorated paper (stained and abrased in places). Smooth spine, with inked title and imprint. Wear to the lower corner of the front cover. Some leaves browned and waterstained. The first leaves mounted on reinforcing paper strips, with old repairs; on fol. a2 a tear without any loss. A few leaves slightly loose. Contemporary marginal notes (partly trimmed), in at least two different early hands.

Provenance: Livio Ambrogio collection.

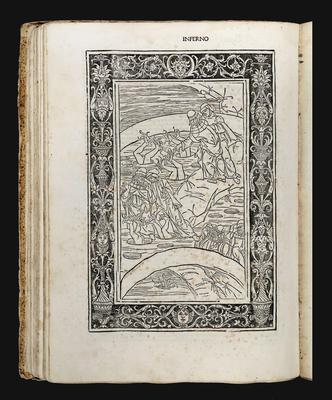

One of the extremely few copies – they can be counted on one hand – of the Brescia Dante containing on fol. l5v (Cantoxix) the woodcut depicting Dante and Virgil looking at the Simoniacs, from the first state of the edition, later replaced – as seen in the preceding description of the other copy in this catalogue – by a repeated and partly modified block depicting the sepulchres of the heretics and Pope Anastasiusii.

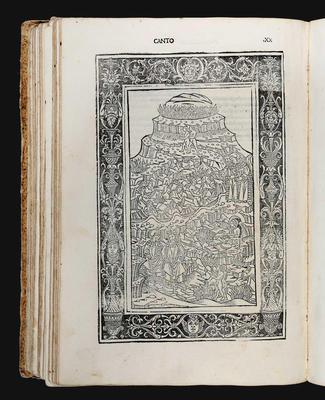

This woodcut shows the Simoniacs – the name comes from Simon Magus, who attempted to buy the gift of the Holy Spirit with money – who are punished in the Third Bolgia. The unknown artist employed by Boninus shows the sinners guilty of simony fixed head downwards in holes in the ground of the bolgia; only their legs are visible. One of the Simoniacs attracts Dante's attention by waving his legs: he is Pope Nicholasiii, who ‘predicts' the wickedness and death of Nicholasv. This is followed by Dante's invective against simoniac popes. The reasons why this illustration was removed to be replaced by a re-used block with some similarities (above all, the round apertures in the ground) are not clear. The original block used for illustrating Cantoxixmight have been damaged or broken, or the printer himself might prudently have decided to suppress it, following the publication on 17 November 1487 of Innocentviii's bull regulating printing, commonly regarded as the first official papal act of censorship. Similarly mysterious are the reasons that forced Boninus to discontinue the illustrations after the first Canto of the Paradiso: perhaps there were technical problems, misunderstandings with the artists or the money ran out. In any case, the replacement and re-use of some blocks in the different states of the Brescia Commedia are evidence of Boninus's increasing problems: in the last cantos of the Purgatorio the same block was used three times, and the woodcut illustrating the first canto of the Paradiso has very little relevance to the content of the canto, revealing the difficulty of devising, canto by canto, adequate pictorial representations for a work which contained an exceptional wealth of new iconographical ideas. Nevertheless the edition was extraordinary in its scope, and provided a visual model for all subsequent fifteenth-century illustrated editions of Dante's masterpiece. Despite lacking the first quire and a few other leaves, the copy described here is of the greatest importance and value for its inclusion of the later suppressed woodcut. The Brescia Dante, in its different states, is not only a fascinating case study for bibliographers and historians, but also a very attractive book for collectors.